This post provides the key points of a journal article I recently had published in The Australian Educational Researcher, co-written with Belinda Hopwood (UTAS), Vesife Hatisaru (ECU), and David Hicks (UTAS). You can read the whole article here

In recent years, there has been increased attention on gender gaps in literacy and numeracy achievement. This is due in part to international assessments of students’ reading achievement such as PIRLS and PISA (Lynn & Mikk, 2009) that have found gender differences in reading are universal, with girls from all participating countries significantly and meaningfully outperforming boys. Previous research has shown that girls score higher on reading tests and are more likely to be in advanced reading groups at school (Hek et al., 2019), while those who fall below the minimum standards for reading are more likely to be boys (Reilly et al., 2019). Large-scale assessments of numeracy have seen similarly consistent results, though with boys outperforming girls. So, what’s the situation in Australia?

Recently, three colleagues and I found out what 13 years of NAPLAN reading and numeracy testing might show about boys’ and girls’ performance in the Australian context. Something that has been lacking from international research has been a clear picture of how reading and numeracy gender gaps become wider or more narrow across the primary and secondary school years. To provide this picture, we drew on publicly available NAPLAN results from the NAPLAN website (ACARA, 2021) and The Grattan Institute’s (Goss & Sonnemann, 2018) equivalent year level technique.

Findings: Gender gap in reading

We looked at the average reading performance of boys and girls across the four tested year levels of NAPLAN (i.e., Years 3, 5, 7, and 9) between 2008 and 2021. Girls improved consistently from Year 3 to Year 9, with approximately two years of progress made between each test. Boys progressed to a similar extent between Years 3 and 5, yet they fell behind the girls at a faster rate between Year 5 and Year 7. Specifically, boys made 1.95 years of progress between Year 3 and Year 5 and 1.92 years between Year 7 and Year 9, but only managed 1.73 years of progress between Year 5 and Year 7 (i.e., in the transition between primary and secondary school).

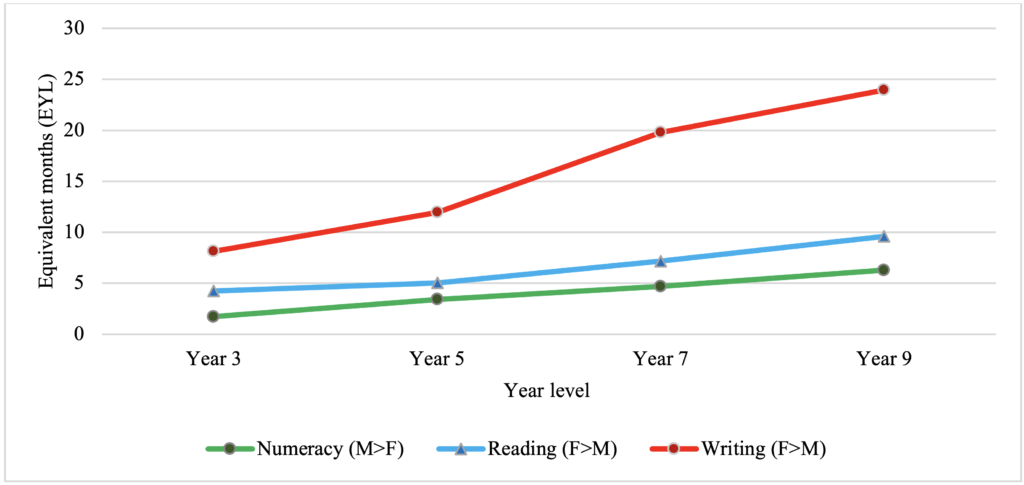

The average gap between boys and girls was wider for each increase in year level, with Year 3 males around 4 months of equivalent learning behind Year 3 females, Year 5 males 5 months behind, Year 7 males 7 months behind, and Year 9 males around 10 months of learning behind Year 9 females. While boys made more progress between Year 7 and Year 9, this was also when girls made most progress. While boys seem to keep up with girls reasonably well in the primary school years, more boys struggle with reading as they transition into secondary school.

Findings: Gender gap in numeracy

The overall picture for numeracy is similar to reading, though with boys outperforming girls and the gender gap increasing across each tested year level. Boys made approximately two years of progress between each numeracy test, while girls consistently made just over 1.8 years of progress between each test, leading to a gender gap that grew wider at a consistent rate over time. Put differently, boys and girls made consistent progress between each numeracy test, though the rate of progress was higher for males, leading to a neatly widening gender gap over time.

What about the writing gender gap?

In 2020, I conducted a similar study that looked into the NAPLAN writing results, finding that on average, boys performed around 8 months of equivalent learning behind girls in Year 3, a full year of learning behind in Year 5, 20 months behind in Year 7, and a little over two years of learning behind in Year 9. Boys fell further behind girls with writing at every tested year level, yet the rate at which girls outperformed boys was greatest between Years 5 and 7. Our study into reading and numeracy has found that similar gaps exist in these domains too, though not to the same extent as writing. For ease of comparison, the following graph shows the extent and development of the gender gaps in numeracy, reading, and writing.

Why do more boys struggle with literacy as they transition into secondary school? For most Australian students, Year 7 is when many (most?) will move physically from their primary school campus to a secondary school campus. This physical transition has been shown to impact student reading achievement, particularly for boys (Hopwood et al., 2017). For some students, their reading achievement stalls in this transition, or in serious cases, declines to levels below that of their primary school years (Hanewald, 2013). Some students entering secondary school have failed to acquire the necessary and basic reading skills in primary school required for secondary school learning (Lonsdale & McCurry, 2004) stifling their future reading development (Culican, 2005). The secondary school curriculum is more demanding and students are expected to be independent readers, able to decode and comprehend a range of complex texts (Duke et al., 2011; Hay, 2014). As argued by Heller and Greenleaf (2007), schools cannot settle for a modest level of reading instruction, given the importance of reading for education, work, and civic engagement. We need to know more about why this stage of schooling is difficult for many boys and how they can be better supported.

The analysis of the numeracy gender gap was quite different from both the reading and writing results. While previous international studies have suggested that the gender gap in numeracy only becomes apparent in secondary school (Heyman & Legare, 2004), this study showed that average scores for boys were higher than those of girls on every NAPLAN numeracy test, though to a lesser extent than the other domains. The widest numeracy gender gap of a little over 6 months of learning in Year 9 was smaller than the smallest writing gender gap of 8 months in Year 3.

Implications of gender gaps in literacy and numeracy

The findings suggest links between reading and writing development, in that more boys struggle with both aspects of literacy in the transition from primary to secondary school. While other researchers have looked at the numeracy gap over time using NAPLAN scale scores (e.g., Leder & Forgasz, 2018), by using the equivalent year level values, we’ve been able to show how the gender gap widens gradually from roughly 2 months of learning in Year 3 to 6 months of learning in Year 9. While this supports the general argument that, on average, boys outperform girls in numeracy and girls outperform boys in literacy tests, it also shows how the gaps are not equal.

References

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2021). NAPLAN national report for 2021. https://bit.ly/3q6NaC4

Culican, S. J. (2005). Learning to read: Reading to learn – A middle years literacy intervention research project. Final Report 2003–4. Catholic Education Office.

Goss, P., & Sonnemann, J. (2018). Measuring student progress: A state-by-state report card. https://bit.ly/2UVNxy5

Hanewald, R. (2013). Transition between primary and secondary school: Why it is important and how it can be supported. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1), 62–74.

Hek, M., Buchman, C., & Kraaykamp, G. (2019). Educational systems and gender differences in reading: A comparative multilevel analysis. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 169-186.

Heller, R. & Greenleaf, C. (2007). Literacy instruction in the content areas: Getting to the core of middle and high school improvement. Alliance for Excellent Education.

Heyman, G. D., & Legare, C. H. (2004). Children’s beliefs about gender differences in the academic and social domains. Sex Roles, 50(3/4), 227-236. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SERS.0000015554.12336.30

Hopwood, B., Hay, I., & Dyment, J. (2017). Students’ reading achievement during the transition from primary to secondary school. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 40(1), 46-58.

Leder, G. C., & Forgasz, H. (2018). Measuring who counts: Gender and mathematics assessment. ZDM, 50, 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0939-z

Lonsdale, M. & McCurry, D. (2004). Literacy in the new millennium. Australian Government, Department of Education, Science and Training.

Lynn, R., & Mikk, J. (2009). Sex differences in reading achievement. Trames, 13, 3-13.

Reilly, D., Neuman, D., & Andrews, G. (2019). Gender differences in reading and writing achievement: Evidence from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). American Psychologist, 74(4), 445-458.