In 2017, Judith Hochman and Natalie Wexler published The Writing Revolution (TWR): a book outlining a new way of thinking about and teaching writing. A key feature that sets TWR apart from other approaches is its suggestion that school students should only focus on sentence-level writing until this is mastered (i.e., the purposes and structures of written genres should only be added after a lot of work on sentences).

This is a somewhat controversial idea if you believe that the sentences we write are always influenced by what and why we’re writing. It also introduces the risk that children will spend much of their primary schooling (and even their secondary schooling, depending on when they start) repeating the same set of basic sentence tasks in every subject. But in taking a developmental approach, Hochman and Wexler argue that learning to write is challenging for young learners, and focusing solely on sentences in the beginning greatly reduces the cognitive load. They say you can’t expect a child to write a strong text, let alone a strong paragraph, until they can write strong sentences. A brief document has been published on the TWR website outlining the theoretical ideas that underpin the approach, which you can read about here.

As I mentioned in my last post on TWR, there haven’t been any research studies or reports to verify if teaching the TWR way enables or constrains writing development… until now.

A reader named ‘Rebecca A’ left a comment on that post to say she’d found a report by an independent research and evaluation firm (Metis Associates) into the efficacy of a TWR trial in New York. The firm partnered with TWR in 2017 and spent some years evaluating how it worked with 16 NYC partner schools and their teachers. Partner schools were given curriculum resources, professional development sessions in TWR, and on-site and off-site coaching by TWR staff.

Evaluating TWR

Metis Associates were interested in TWR writing assessment outcomes, outcomes from external standardised writing assessments, and student attendance data. They compared the writing outcomes of students at partner schools with the outcomes of children at other schools. Teacher attitudes were also captured in end-of-year surveys.

This report did not go through a rigorous, peer-reviewed process, but if you are interested to know if TWR works, it’s probably the best that’s currently out there. Also, keep in mind that the partner schools were very well supported by the TWR team with resourcing, PD, and ongoing coaching. In that sense, you might consider this a report of TWR under ideal circumstances.

If you work at a school using TWR or if you’re interested in the approach, I’d recommend reading the full report here. I will summarise the key findings of the report in the rest of this blog post.

Key finding 1: Teacher attitudes

Teachers at partner schools reportedly found the TWR training useful for their teaching and got the most value from the online TWR resource library. School leaders liked being able to reach out to the TWR team for support if necessary. Some teachers wanted more independence from the strict sequence and focus of TWR activities. Most though found the approach had helped them to teach writing more effectively.

Key finding 2: Impact of TWR on student writing outcomes

But what about the development of students’ writing skills? TWR seems to have made a positive difference at the partner schools. TWR instruction helped students in each grade to advance somewhat beyond the usual levels of achievement. It’s not possible to say much more about this since the presentation of results is quite selective and we only see how the partner schools compared with non-partner schools for certain statistics, like graduation rates and grade promotion rates, which are likely influenced by all sorts of factors. The one writing assessment statistic that does include comparison schools is for the 2019 Regents assessment for students in Years 10, 11, and 12. In this case, those at TWR schools did better in Year 10, results between TWR and comparison schools were similar in Year 11, while comparison schools did better in Year 12. So, a mixed result. Being behind other schools is not really an issue if everyone is doing well, but it’s not immediately clear from this report how these results compare with grade-level expectations or previous results at the same schools.

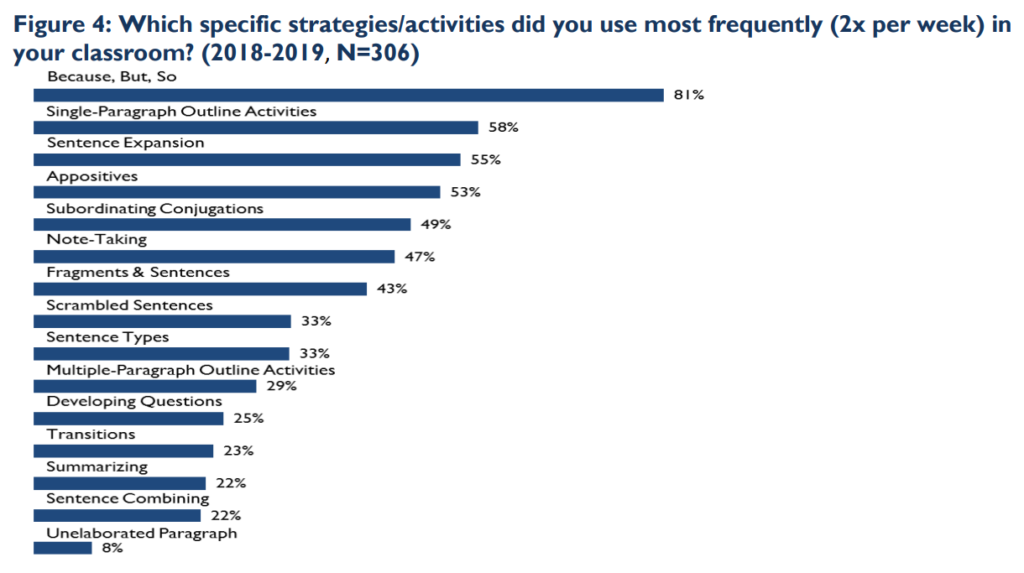

Something that might explain the mixed outcome for senior secondary students is the tendency for teachers at partner schools to favour the basic sentence level strategies over paragraph or whole text/genre strategies in their teaching. Partner schools taught TWR in Year 3 through to Year 12, and 81% of teachers reported teaching the “because, but, so” strategy regularly (i.e., more than 2 times per week). By comparison, evidence-based strategies like sentence combining were far less commonly taught (i.e., regularly taught by 22% of teachers). This suggests that it’s important for schools using TWR to be systematic and intentional about the strategies taught and to ensure that you aren’t spending longer than needed on basic sentence-level activities so you can get the most important of what TWR offers, which I would argue comes with the single and multiple paragraph outlines and genre work.

When only looking at partner school outcomes, the picture looks positive. The report shows percentages of students performing at Beginning, Developing, Proficient, Skilled, and Exceptional levels at the beginning and end of the year. At each partner school, percentages are all heading in the right direction with many more proficient and skilled writers at the end of the evaluation.

Conclusion

To summarise, in offering select outcomes and comparisons only, and in using metrics that aren’t entirely clear, the report highlights the need for rigorous, peer-reviewed studies to better understand how TWR works for different learners and teachers in different contexts. Despite its limitations, the report points to positive outcomes for the new approach to teaching writing. This is good news for the schools out there that have jumped on board the TWR train.

It also suggests that careful attention should be paid to the specific TWR strategies that dominate classroom instruction if students are to get the most out of it. If you are using the TWR approach, my advice would be not to spend a disproportionate amount of time on basic sentence work from the middle primary years, since well-supported approaches like SRSD and genre pedagogy have shown students can (and should?) be writing simple texts that serve different purposes from a young age.

I remain greatly intrigued by TWR. It turns the writing instruction game on its head and has made me question whether other approaches expect too much from beginning writers. Its approach seems to line up nicely with cognitive load theory, in gradually building the complexity and expectation as learners are prepared for it. There’s a lot at stake though if this specific combination of strategies doesn’t actually prepare students for the considerable challenge of genre writing in the upper primary and secondary school years. You could follow its strategies diligently across the school years but inadvertently limit your students’ writing development (in time, more research will tell us if this is the case).

I realise it’s anecdotal, but my 7-year-old son (just finished Year 1) and I have been talking about argumentative/persuasive writing at home for the last few weeks and the discussions we’ve had and the writing he’s done as a result have been incredibly satisfying for both of us. To think that he should be limited to basic sentence writing and not think about and address different purposes of writing

(like persuading others about matters of personal significance) for years into his primary schooling wouldn’t sit well with me after seeing what he’s capable of with basic support grounded in a firm knowledge of language and text structures and encouragement.

It’s also possible to see how students who struggle badly with writing could benefit from practice with basic sentence writing before much else. It was in a context filled with struggling writers that TWR was first conceived, and that it may be most useful.

I’m looking forward to additional research being conducted about TWR. If any schools using the approach are able to comment on its usefulness in your context, that might be helpful for others thinking about giving it a go.

References

Hochman, J. C., & Wexler, N. (2017). The writing revolution: A guide to advancing thinking through writing in all subjects and grades. Jossey-Bass.

Ricciardi, L., Zacharia, J., & Harnett, S. (2020). Evaluation of

The Writing Revolution: Year 2 Report. Metis Associates. https://www.guidestar.org/ViewEdoc.aspx?eDocId=1956692

Thank you!

Highly informative summary.

No worries, Ed. Thanks for reading and take care.

Damon

I came across a link to this post on Twitter, and — since I’m one of the co-authors of The Writing Revolution book — I naturally read it with interest! I appreciate your efforts to evaluate the method, but I’d like to add a few thoughts that I hope will clear up some apparent misinterpretation of what it calls for–which probably stems from a lack of clarity in the book (there’s a second edition in the words that I hope will be clearer). I believe the trainings offered by the The Writing Revolution organization provide more clarity, but it would be best to have a few things better explained in the book itself.

The main point that gets misinterpreted is the idea that TWR requires limiting students to sentence-level writing “until this is mastered,” as you say. In fact, all the method recommends is that students don’t engage in INDEPENDENT lengthier writing until they’ve acquired some ability to construct sentences. But they can and should engage in activities like outlining paragraphs while they’re still learning the mechanics of sentence construction.

With less experienced or younger writers, this can be done orally and collaboratively. I once saw a class of kindergartners collectively outlining a paragraph on why Play-Doh is such a great toy, with their teacher writing their ideas on the board. They were learning how to craft a topic sentence and connect supporting details to it in a manageable way that will serve them well when they’re ready to do that independently (and they were also deeply engaged in the activity!).

So I would disagree with your comment that teachers should ensure they’re not spending too much time on sentence-level activities, because outlining and genre work is really the important part of the method. You can do these things simultaneously, to some extent, as I’ve described above, but teachers will need to evaluate what their particular students are ready for. If they’re still inexperienced at constructing sentences, asking them to write at length will probably be counter-productive because it will place too heavy a burden on working memory.

Undoubtedly there are some 7-year-olds, like your son, who are experienced or able enough writers to write at length. I had a 7-year-old like that, too! But of course there are many, many 7-year-olds, and even quite a few 17-year-olds, who are not in that position. As we say in the book, teachers need to differentiate: the students who need sentence-level activities should get them, regardless of age or grade level, and others who are ready for lengthier writing can be working on that. The key is that they’re all writing about the same content.

At the same time, it’s also important to bear in mind that, as Judy Hochman says, the rigor of the activity depends on the content. Even sentence-level activities can be intellectually challenging. Consider this: “Immanuel Kant believed that space and time are subjective forms of human sensibility, but _____________________.”

There is, by the way, a key difference between activities like sentence-combining and other sentence-level work, like “because, but, and so.” The latter actually go beyond teaching the mechanics of sentence construction to build and deepen students’ knowledge, because students need to supply missing information. Yes, there’s been research on sentence-combining, but we need more research into the knowledge-building kind of sentence-level assignments.

Speaking of research, you may be interested to know that there is now an ongoing research project into the impact of TWR in the U.S., designed and carried out by a highly respected third-party organization called Mathematica. So stay tuned for the results, in time.

Dear Natalie,

Thank you for taking the time to read the post and offer a generous and thoughtful response. It makes good logical sense that we shouldn’t ask students to engage in lengthy independent writing until after they can construct sentences adequately. The genre work is very important too if we’re to set children up for success as they transition from primary/elementary to the much more linguistically and rhetorically demanding high school years. TWR has this necessary emphasis on genre eventually, but, at least in my reading of the book and the training I completed with the good folks from TWR in the US, there was a strong sense that genre should be set aside until students are crafting strong sentences.

There’s a risk that this presents sentences as being somehow independent or separate from genre and the notion that we make different writing choices to meet different purposes (even when writing sentences). Indeed, the Immanuel Kant example you included would clearly suit an information report or argument genre more than a procedural text or a narrative. All the sentence-level work teaches the building blocks of genres, though, at least in my reading, this doesn’t become explicit in TWR until students are crafting paragraphs.

If you did want to tie the sentence-level work to genres in an explicit way, you’d likely run into the issue of needing many more sentence strategies than what’s in the current version of the book. There are many varied ways to construct sentences in English, and sentences in one genre are often quite different in another. We have such a method in Australia named genre-based pedagogy, underpinned by a rich theory of language, which has been the dominant approach for teaching writing here since the 1990s. Unfortunately, genre pedagogy requires a strong knowledge of language to teach it well, and many students are simply taught the same basic (recipe-style) text stages every year of school and never get down to the sentence- and clause-level grammar that is needed for many students who struggle with writing.

For TWR, none of this matters if the sentence strategies you’ve selected do set children up to (eventually) write in all sorts of genres. I guess we’ll know more about that after additional research and independent evaluations.

There is a chance I’ve misinterpreted your writing and I do apologise if that’s the case. I found your book entirely thought-provoking and I’ve watched with interest as schools in Australia have taken it on as a whole-school approach to writing. It’s excellent to hear that further evaluations are underway. Some peer-reviewed research comparing TWR to other popular approaches like SRSD are essential too if we’re to make confident recommendations to schools based on evidence.

Thanks again and take care!

Your explanations are very helpful–thank you. As someone who has taught every grade level K-12 (that’s Play-doh to Plato), there is so much to appreciate about TWR, but I am definitely concerned that the recommendations for emphasizing sentence-level writing for K-1 students might be misconstrued by some teachers. The research by Ouellette and Senechal shows how writing improves reading because it provides students with opportunities to apply their letter-sound knowledge when segmenting words. Kids need lots of opportunities to write to facilitate future reading.

Asking kids to master the sentence without simultaneously being allowed to write ‘furiously’ seems like the wrong advice–in some instances. At this level kids are doing writing that’s ‘conversational’ rather than ‘presentational’, and–yes–we want to introduce the structural sequences that nudge them towards presentation, but I have found that allowing students the joy of this fluency–while also teaching sentence structure that they will apply to a future draft (if not for this piece, certainly for many others)–makes for motivated writers. It seems paradoxical that the burden of ‘cognitive load’ is used to describe writers who struggle with maintaining spelling and sentence structure within extended writing–which I understand is very real–and yet there can also be a cognitive load for emergent writers who struggle to get their thoughts down if they have to worry about ‘correctness’ now rather than later.

I appreciated the exchange you had with Tim Shanahan on his blog, “My First Graders Aren’t Producing Much Writing? Help!” https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/my-first-graders-arent-producing-much-writing-help#sthash.0zmKYDT7.Bdw9qzjd.dpbs

This is an important discussion!

“To think that he should be limited to basic sentence writing and not think about and address different purposes of writing (like persuading others about matters of personal significance) for years into his primary schooling wouldn’t sit well with me after seeing what he’s capable of with basic support grounded in a firm knowledge of language and text structures and encouragement.”

This is precisely what I keep thinking of. TWR discourages having first graders write ‘furiously’, but when I think of the joy that my kindergartners and first graders experienced when sharing all their thoughts on a topic, I realize that there is a place for allowing (furious) fluency in expression and also reigning in that fluency with careful instruction in sentence structure. Not ‘either or’ but ‘both and’?

Thanks for this reply, Harriett,

Yes, I think it’s definitely a case of ‘both and’. There are many important ways to engage children in genre-related learning in the early primary years, such as through oral language, drawing, and acting/performing, in addition to developmentally appropriate writing tasks. In a similar way to parents reading children picture books before bed, this helps them learn patterns of meaning that are useful when you’re communicating with others for all sorts of purposes (e.g., explaining, entertaining, informing, persuading, instructing, etc.). As you’ve suggested, there will also be times when you can let younger children go to write longer texts. It’s about knowing your students and what they’re ready for.

All the very best!