The release of NAPLAN test results always sparks conversations and debates about the state of education and student performance. The 2023 results are no exception, but this year’s results come with a twist that makes comparisons even more intriguing. With NAPLAN testing shifting to two months earlier in the school year (from May to March), it was expected that student results would be lower than in previous years (when students had two months of additional learning to influence test preparation). Of course, it doesn’t make much sense to compare the test results in 2023 with any of the previous tests (which began in 2008), since we would be comparing ripe apples with slightly less ripe apples. But I decided to go ahead and compare the 2023 results with the 2022 results anyway, just for fun, split up by gender. Some of the findings were definitely unexpected!

Reading and Writing: A Mixed Bag

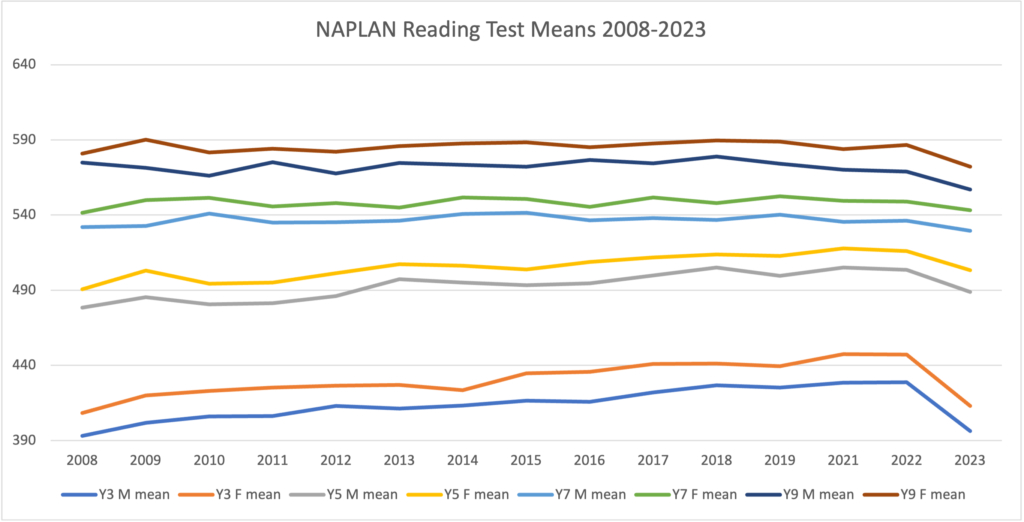

The 2023 reading results for male and female students in every tested year level (i.e., Years 3, 5, 7, and 9) all showed a downward trend compared to the 2022 results. This can likely be attributed to the earlier testing date, with 2023 students having less time to develop reading skills before the test.

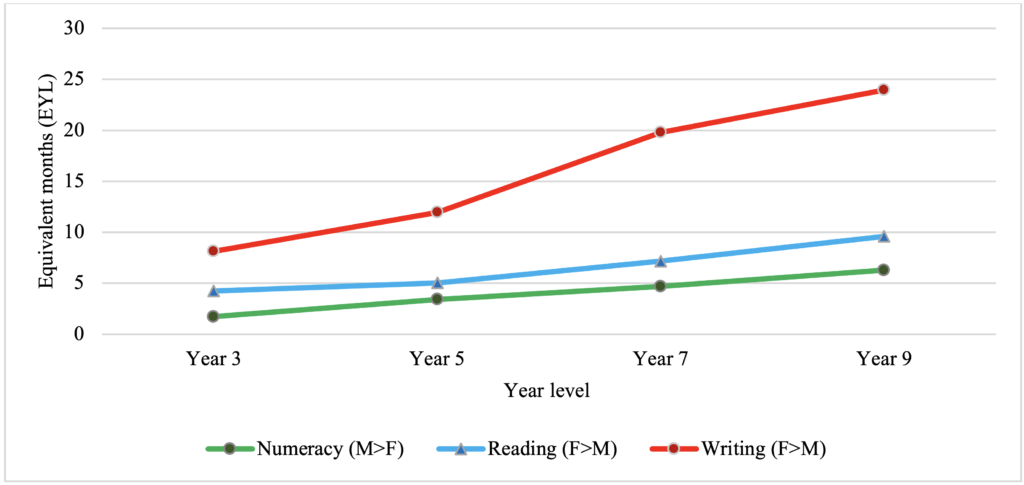

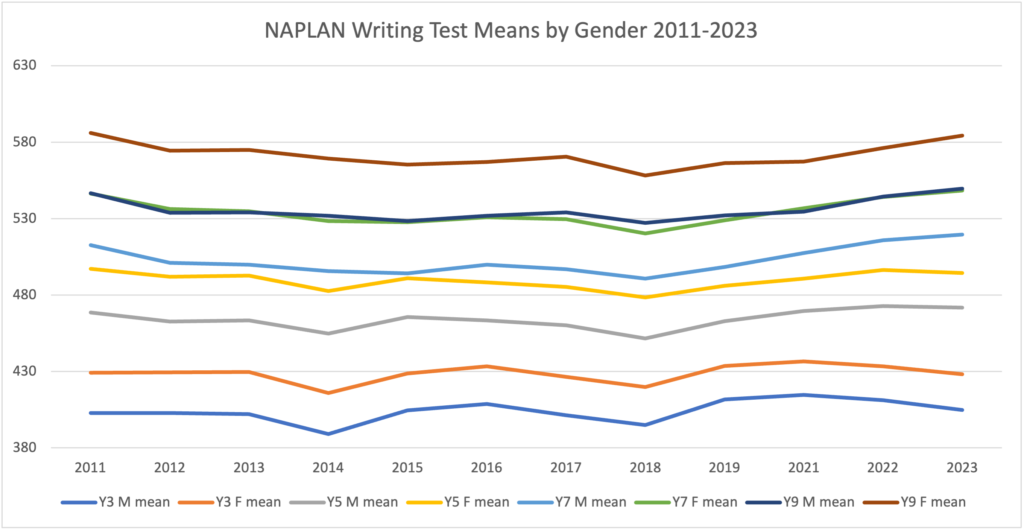

There was a dip in writing results among primary school males and females that mirrored this trend, as was expected. However, in a fascinating twist, writing scores actually improved for male and female students in Year 7 and Year 9. In fact, compared to all NAPLAN writing tests since it was modified in 2011, the 2023 scores were the highest ever for Year 7 males and females and Year 9 males, while for Year 9 females it was their second highest. How is this possible? Could something have changed in the marking process? This is unlikely since nothing like this has been discussed by ACARA. Did secondary school students find the 2023 writing prompt easier to address in the limited test time? This is somewhat plausible. Could secondary school students be feeling more positive about NAPLAN testing in March than in May? Without more information, it’s not possible to know what has driven this marked increase in secondary writing test scores. But it’s certainly odd that students with two fewer months of preparation would perform higher on a test that, for all intents and purposes, seems equivalent to all recent writing tests.

Despite the positive news for secondary students, it should be pointed out that Year 9 males are still performing at a level equivalent to Year 7 females, demonstrating a persistent gender gap that merits further investigation. Year 9 males performed more than two years of equivalent learning behind Year 9 females (i.e., 24.12 months – yikes!).

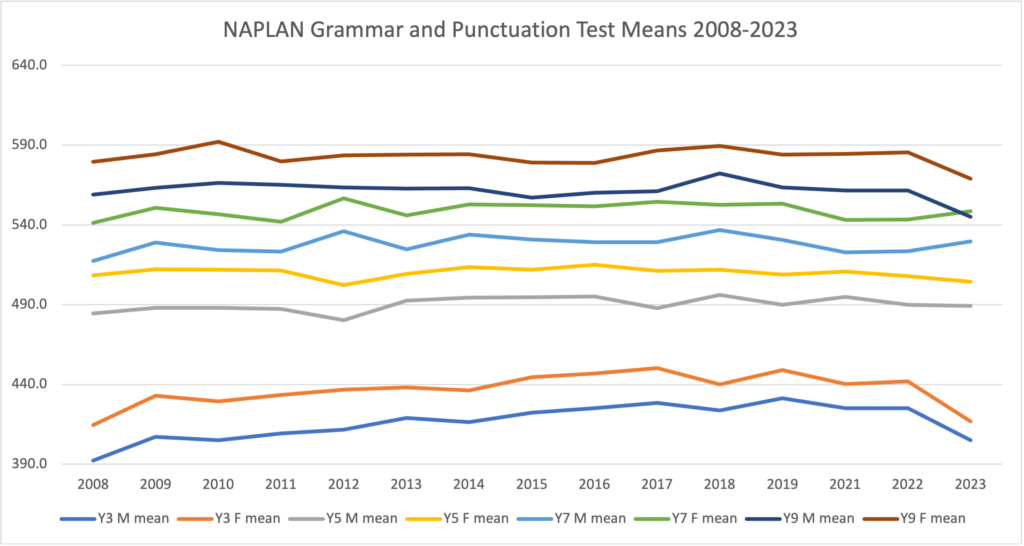

Spelling and Grammar: Heading Down

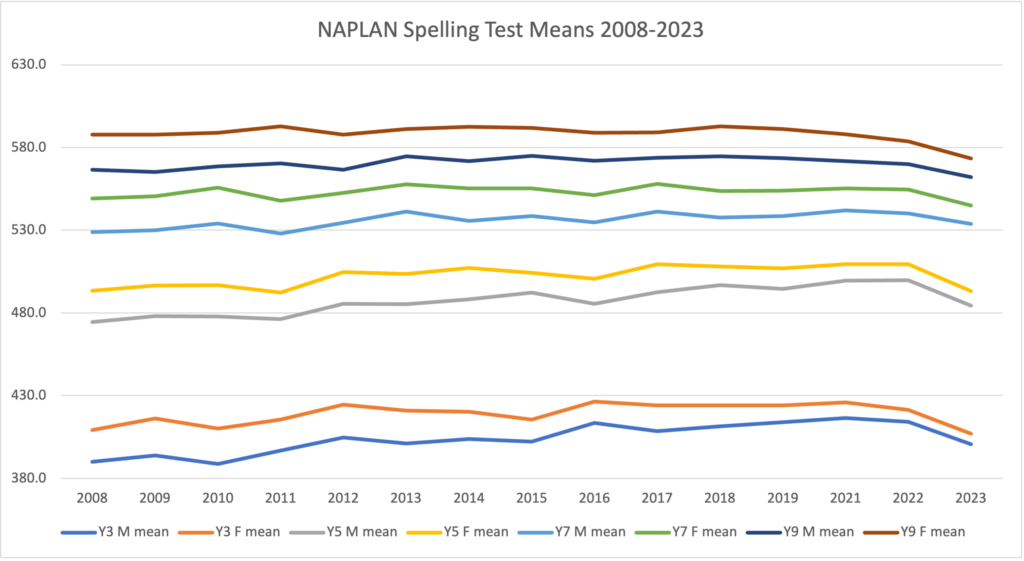

Like reading, spelling scores were down for males and females in all tested year levels. Again, this was expected given the shift to earlier testing.

Grammar and punctuation results mostly followed the same downward pattern, with Year 3, Year 5, and Year 9 males and females all achieving lower scores than the 2022 students. Strangely, grammar and punctuation scores for Year 7 students from each gender were higher than Year 7 students who sat the test in 2022.

As a noteworthy point from the data, Year 7 females outperformed Year 9 males for the first time in any NAPLAN grammar and punctuation test (or any NAPLAN literacy test). This can be explained by the considerable (but expected) decline in Year 9 male scores, while Year 7 female performance was somehow largely consistent with recent years, even with the earlier testing.

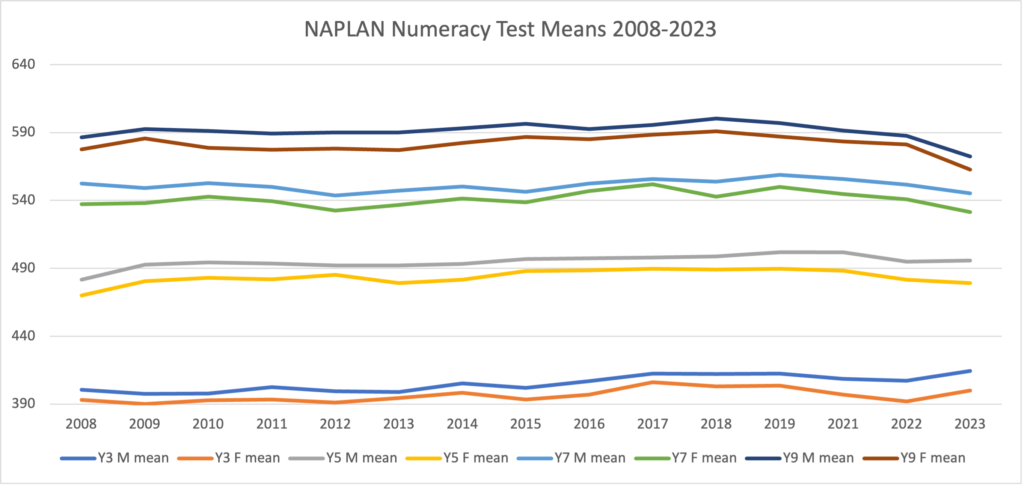

Numeracy: A Glint of Improvement

In terms of numeracy, all primary school males and females somehow scored higher than their 2022 counterparts (except for Year 5 females whose scores in 2023 were slightly down). Surely the numeracy test and its marking procedures haven’t changed, so it’s unclear why there would be clear improvements. Year 3 males managed to achieve their highest mean score of any previous NAPLAN numeracy test. With two fewer months of class time 🤷♂️

On the other hand, secondary school students, regardless of gender, scored lower than the 2022 students. But again, this was expected, so no alarm bells yet.

Final Thoughts: Beyond the Numbers

While the 2023 NAPLAN results might not be directly comparable to previous years due to the changed testing timeline, they offer valuable insights into the dynamics of education and student performance. The interplay of gender, year levels, and subject areas provides a rich tapestry of information that policymakers, educators, and researchers can draw from to tailor interventions and strategies.

It was kind of shocking to see that in specific areas, the earlier 2023 testing procedure resulted in higher scores (i.e., secondary writing and primary numeracy). That said, all students would clearly benefit from the additional two months of learning about reading, spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

The 2023 results highlight the importance of considering the broader context surrounding NAPLAN test scores. As we move forward with this whole new world of NAPLAN testing, complete with four shiny new proficiency standards that replace the previous bands, it will be as intriguing as ever to see the rise and fall of student results across the country. These broad pictures of student achievement would not be possible without NAPLAN testing.